Alois Riklin

Veracity in Politics

Farewell Lecture

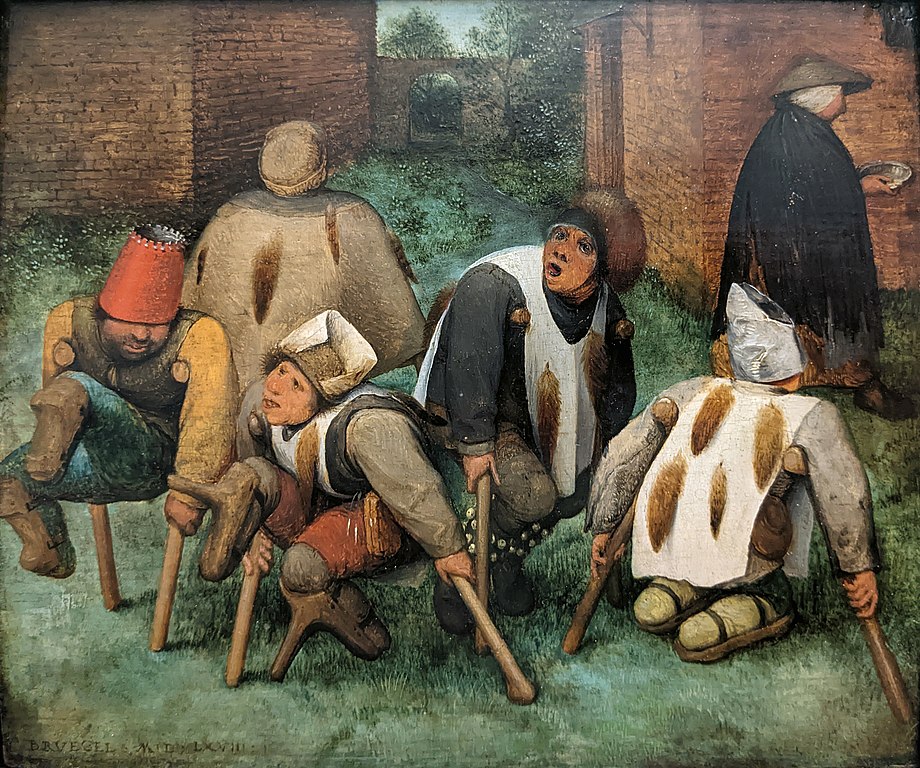

The Lies walking like cripples on the crutches

Farmer (cap)

Soldier (helmet) - Citizen (fur cap)

Aristocrat (crown) - Clergyman (miter)

The Beggars - Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Musée du Louvre, Paris

About the author -

Alois Riklin,

born 1935, Dr.iur., 1970-2001 professor for political science at the University of St. Gallen, founder and

director of the institute for political science, 1982-1986 rector of the St. Gallen University.

(c) Alois Riklin, St. Gallen, 2001

special edition by Stämpfli Verlag, Bern

(a)web/pdf re-edition courtesy of the author (a)

for Czech and Slovaks building up democracy

(a)

web :

vjrott.com/veracity-in-politics

/ pdf download :

vjrott.com/veracity-in-politics.pdf

Table of contents

Veracity in Politics

1 Positions in moral philosophy

1.1 The absolute prohibition of

lying

1.2 The permissibility of lying

1.3 The partial permissibility of lying

2 A typology of practical cases

2.1 Legitimate untruthfulness

Untruthfulness out of courtesy or consideration

Suppression, discretion, and secrecy

Ambiguity and secret reservation

White lie to save life and limb

Stratagems

2.2 Illegitimate untruthfulness

Qualified mental reservation

Unlawful word of honour

Electioneering fraud

Disinformation of parliament and the people

Rigged elections

Broken promise

Politician's official lie

Perjury before a parliamentary investigation committee

3 Incentives for truthfulness

3.1 Person-oriented political ethics

3.2 Institution-oriented political ethics

3.3 Results-oriented political ethics

Conclusion

Bibliography

Veracity in Politics

Truthfulness in politics: is there such a thing? Is this

not a contradiction in terms? Isn't politics a dirty

business? Politics has to do with power, and is not power as

such evil, as Jacob Burckhardt thought? (1)

Didn't Niccolò Machiavelli recommend that whoever

wants to remain a good Christian, indeed a good human being,

should keep his distance from politics? (2)

Didn't Hannah Arendt write in her book Wahrheit und

Lüge in der Politik [Truth and Lying in

Politics]: "Truthfulness has never numbered among the

political virtues, and lying has always been permitted as a

political instrument"? (3)

Didn't Niklas Luhmann argue that political systems are not

meant to be checked on the basis of ethical criteria? (4)

Didn't he say that whoever entered the level of politics

would ineluctably face the dilemma of moral

naïveté or moral cynicism. (5)

Luhmann decided in favour of cynicism: if a politician is

caught lying, he will be sacrificed so that everything else

can continue to run its course unchanged. (6)

Didn't Hans-Georg Soeffner outline an equally cynical

representation theory whereby we delegate the dirty business

of politics to elected representatives so that we ourselves

will be able to wash our hands of it? (7)

And did not Jean-François Revel write: "The very

first of all the forces that govern the world is the lie"? (8)

However, it is not entirely true that truthfulness has

never numbered among the political virtues and that lying

has always been permitted as a political instrument. The

virtue of veracity and the vice of mendacity in general,

including the realm of politics, have often been discussed

in the history of ideas, in the Bible, by Aristotle (9),

by St Augustine (10),

by St Thomas Aquinas (11)

and by Kant (12),

to name but some of the most important sources. Still, any

express application to politics is somewhat rare; it is most

likely to be found in the so-called Mirrors of Princes, for

instance in the Mirror written by Aegidius Romanus. (13)

Unlike the cardinal virtues of justice (iustitia),

self-control (temperantia), strength

(fortitudo) and good sense (prudentia),

veracity (veracitas) is hardly ever found in the art

of politics, either. In most recent times, two authors in

particular have expressly treated truthfulness in politics:

the Harvard philosopher Sissela Bok (1980) and Freiburg's

moral theologian Eberhard Schockenhoff (2000).

Then again, the first political thinker who, in the long

history of political ethics, conceived of veracity as a

central problem of politics, is a contemporary: our honorary

doctor Václav Havel. In 1978, between his first

arrest and two later spells in prison, he wrote a courageous

book entitled Versuch, in der Wahrheit zu leben

[An attempt to live in truth]. (14)

In this book, Havel condemned the mendaciousness of the

post-totalitarian communist system and chose for himself the

way of truthfulness, irrespective of the high risks of false

imprisonment, professional discrimination and social

ostracism. Havel did not one-sidedly regard the powers that

be as guilty of lying; rather, he located the diabolical

aspect of the post-totalitarian system in the fact that it

turned victims into accomplices: by threatening them and

their descendants with disadvantages, it coerces the victims

to participate in it. When Havel had become president, he

reminded his fellow citizens of their complicity arising

from their coming to terms with life in lying. (15)

Consequently, he exhorted them in his address before the

first democratic general elections to vote for candidates

who "are used to telling the truth and do not wear a

different shirt every week". (16)

Havel was primarily thinking of life under a totalitarian

system where - to speak with Orwell - the Ministry of Truth

rewrote even history to make it fit the prevalent

circumstances. Yet in asides, Havel left no doubt that he

did not consider the reality evinced in democratic countries

to be flawless by any manner of means. (17)

Indeed, the lies that have been told by politicians and then

been brought to light in the most recent times, particularly

in big countries, are shocking. Cases in point are the

Rainbow affair in France, the Spiegel, Barschel, Engholm and

party donation scandals in Germany, and the Pentagon Papers,

Watergate and Irangate in the US.

I shall now proceed to describe the positions in moral

philosophy, then develop a typology on the basis of

practical cases, and finally outline incentives for

truthfulness in politics.

1 Positions in moral philosophy

Lying is not the sole deviation from truth. St Thomas

Aquinas classed truthfulness as one of the common virtues

and contrasted it, not only with lying, but also with

hypocrisy and boastfulness. (18)

This, however, is far from covering the entire field of

untruthfulness, whose further facets include perjury, false

promises, disinformation, dissimulation, guile, breach of

promise, palliation, flattery, pretexts, distraction,

suppression of important information, secrecy, obfuscation,

forgery, deception, and manipulation by means of

advertising. Montaigne wrote that the opposite of veracity

was a boundless field containing a hundred thousand

varieties. (19)

Yet lying is the clearest and most conspicuous form of

untruthfulness, and this is why moral philosophy has focused

on the lie as the nucleus of untruthfulness, lying conceived

as a false statement or a false sign made with intent to

deceive.

Three positions are to be discerned in moral philosophy:

the absolute prohibition of lying, the basic permissibility

of political lying, and its partial permissibility.

1.1 The absolute prohibition of

lying

The first author of antiquity to deal systematically with

lying was St Augustine. (20)

He differentiated between eight levels of lying. Yet he

regarded any lying as sinful, even a lying that would harm

no one or protect someone innocent. The Bible and the church

fathers were his main sources. Christ said in the Sermon on

the Mount: "But let your communication be, Yea, yea; Nay,

nay: for whatsoever is more than these cometh of evil"

(Matt. 5, 37). John calls the devil "the father of the lie"

(John 8, 44). The Old Testament, however, gave St Augustine

more of a headache than the New. Of course, he was able to

refer to the Eighth Commandment (Ex. 20, 16) and to the

numerous complaints about falsehood in the Psalms (e.g. Ps.

5, 7). But what should be thought of the false reports in

the Old Testament, and particularly of the "most refined

staging of a successful feint" (21)

when Jacob, at the instigation of his mother, Rebecca, made

his blind father, Isaac, believe that he was the elder

brother, Esau, thus obtaining the firstborn's inheritance by

false pretences? (Gen. 27, 1-40) Augustine solved the

problem presented by such biblical passages with the pious

explanation: "Non est mendacium, sed mysterium."

Immanuel Kant represented the same rigorism, not on

theological grounds, but on the basis of the ethics of

reason. (22)

Benjamin Constant had attacked him on that score. (23)

Kant replied with a small work entitled Über ein

vermeintes Recht aus Menschenliebe zu lügen [On

a putative right to lie for the love of mankind], (24)

in which he quoted the standard case, brought into play by

Constant, of the potential murderer who wants to be told

whether his intended victim is inside the house. According

to Kant, even the person thus addressed by the potential

murderer is obliged to tell the truth. The obligation of

veracity applies regardless of any consequences. Lying "is

the waste and, as it were, destruction of his human

dignity". (25)

1.2 The permissibility of lying

St Augustine and Kant did not set their sights on

political lying, but it was implied. With a view to

political lying, Plato and Machiavelli defended the opposite

position. In his Politeia, Plato granted the

philosopher kings the right to lie in the interest of the

state. They, and they alone, were allowed to tell lies in

order to safeguard the ideal state. (26)

If subjects tell lies, they will have to be punished for it.

The powers that be, however, may spread the false tale that

God had admixed the rulers with gold, the guardians with

silver, and the providers of food with iron ore. (27)

For the purpose of human breeding, they may also deceive

couples by letting them believe they had met by chance

whereas in fact they had been brought together with intent. (28)

An even more general justification of political lying and

untruthfulness was provided by Machiavelli in his

Principe (29):

the prince must be a "master of hypocrisy and

dissimulation"; he does not keep promises if that is

detrimental; since people are evil and bad, the prince is

entitled to break his word; people are so stupid that every

fraudster will find someone to defraud; it is neither

possible nor necessary for the prince to have all the

virtues - indeed, it is positively harmful to have them all

and use them all the time: the appearance of virtues is

sufficient. The Principe's motto is "seeming, not

being": the inversion of Cicero's "being instead of

seeming". (30)

By way of a role model, Machiavelli recommended Cesare

Borgia, one of the biggest crooks in the history of the

world. He admired the sang froid with which Cesare

lured his disloyal condottieri into a trap in

Sinigaglia under the guise of friendship and killed them one

after the other (31)

- an atrocity which would serve Hitler as the model for the

Röhm putsch. (32)

1.3 The partial permissibility of

lying

The intermediate position of the partial permissibility

of lying is equivocal. In early modern times, it was

particularly Hugo Grotius (33)

and Samuel von Pufendorf (34)

who investigated the problem and set up boundaries on either

side. Since then, moral theologians and moral philosophers

have found exemption rules in great numbers and have

permitted lies:

- if they are told in an extreme emergency,

- if they will result in great benefits, or prevent great damage,

- if they are told for reasons of humility or modesty,

- if their intention and purpose are good,

- if there is no intention to deceive,

- if the person to whom the lie is told has no right to be told the truth,

- if it is told for reasons of courtesy or in consideration of human frailty,

- if it will not harm anybody,

- etc. (35)

The former Bishop of Chur and present Archbishop of

Liechtenstein, who for a time adorned his name with the

letters indicating a doctor's degree which he had never

acquired, thought he would be able to exculpate himself by

saying that it had not harmed anyone...

Sissela Bok also permits exemption from the prohibition

of lying, but those do not go as far as the list adduced

above. Political lying, in particular, is measured against a

very severe yardstick. Contrary to Plato and Machiavelli,

she maintains that a government's position does not make

telling lies any more honourable. (36)

She scrutinises the usual excuses (37)

and then rates them according to their justifiability. (38)

First, it must be examined whether there is an honest

alternative to lying. Then, the lying must be subjected to a

public test, i.e. a fictitious discussion such as can be had

among reasonable people. (39)

The method is reminiscent of Immanuel Kant, John Rawls, and

discourse ethics.

Sissela Bok does not believe that these problems can be

solved in abstract terms. By that token, she also rejects

the utilitarian approach which determines the permissibility

of lying on the basis of beneficial consequences alone.

Rather, she prefers following the Stoics, Talmudists and

early Christian thinkers and tackling the problem on the

basis of concrete cases. (40)

The following typology will also be based on practical

cases.

2 A typology of practical cases

I shall first deal with some cases of legitimate

untruthfulness, followed by some that strike me as

illegitimate. In doing so, I shall admit forms of

untruthfulness which are not lies in the defined sense of

the word.

2.1 Legitimate untruthfulness

Untruthfulness out of courtesy or

consideration

The courtesies that are customary in diplomatic relations

are harmless, just as everyday restraint for reasons of

human consideration does not yet constitute hypocrisy. (41)

Truth can be hurtful, indeed offensive. We need not tell

every fool to his face that he is one.

Suppression, discretion, and secrecy

The case collection of Harvard University includes the

following occurrence. (42)

On the occasion of the Cuba crisis in 1962, the two

superpowers were facing the abyss of direct military

confrontation. The Soviet Union was about to establish a

nuclear missile base in Cuba. The US demanded that the base

should be closed down, and set up a blockade against Soviet

freighters. At the climax of the crisis, Khrushchev made an

offer to John F. Kennedy in a letter that the USSR would

give up the Cuban base if, by way of countermove, the US

withdrew the nuclear missiles stationed in Turkey. Now, the

American President had ordered the close-down of the missile

base in Turkey twice before; however, the order had not been

carried out because the Turkish government opposed it.

Kennedy did not regard it as politic to accept the Soviet

offer since such a deal might raise doubts among the

European allies as to whether the US nuclear umbrella over

Western Europe had any permanence. Kennedy decided to reply

to a previous letter of Khrushchev's and to propose that the

US would not invade Cuba. At the same time, he unofficially

sent his brother Robert to the Soviet UN ambassador, Anatoly

Dobrynin, with the private message that the President had

already ordered the withdrawal of the nuclear missiles from

Turkey and that he gave his assurance that this order would

be carried out speedily. Khrushchev gave in. Subsequently,

Kennedy was asked at a press conference whether the US had

made any concessions with regard to disarmament. The

President's answer was negative; he said that he had

instructed the negotiators to limit themselves exclusively

to Cuba and that no other questions had been discussed.

This reply was true, but it was incomplete. Strictly

speaking, there had not been any bartering of base against

base. But Kennedy suppressed that he had unofficially given

his assurance that the missiles would now be withdrawn from

Turkey without any delay. The President had not made a

concession but confirmed a decision he had made earlier.

This suppression was risky, but not contrary to the truth.

No one, not even a politician, is obliged to tell everyone

else the whole truth at any time. Unlike a witness in a

criminal trial, we are not obliged "to tell the truth, the

whole truth and nothing but the truth". We would not have

won the popular ballot for the extension building of our

University if we had not carefully suppressed our weak

points.

This does not mean that suppression, discretion and

secrecy are justified in every case. Secretmongering can

also be exaggerated, which is what Pericles criticised the

Spartans for in his funeral oration for the Athenians who

had fallen in the first year of the Peloponnese War. During

the time when I served in the Swiss Army, I had the

impression that secrecy was exaggerated. Virtually every

order could have been classified one level lower.

Aargau's senator Julius Binder made a move along these

lines in parliament. Conversely, a joker proposed that a

fifth level of secrecy should be introduced: "For service

use only", "Confidential", "Secret" and "Top secret" should

be supplemented by the new and highest level called "Destroy

before reading"!

Ambiguity and secret reservation

Galilei stated in the ecclesiastical inquisition trial

that he had never believed that Copernicus was right. When

he was saying that, however, he was secretly thinking that

he did not believe but knew that the earth revolves around

the sun and not vice versa. In this way, he ensured that he

was given a milder punishment. It is quite possible that the

circles around Cardinal Bellarmin realised what Galilei was

up to. His secret reservation was legitimate since the

inquisition court was not entitled to force anyone to revoke

the results of scientific research. Meanwhile, the Roman

Catholic church has had to acknowledge this, too, in that it

has rehabilitated Galilei in a highly embarrassing and

lengthy proceeding, with a delay of nearly four hundred

years.

The secret reservation was brought into discredit,

particularly among Protestants, under the term mental

reservation, after Pascal, in his ninth Lettre

provinciale had launched a polemic against "Jesuit"

craftiness. (43)

Again, this does not mean that ambiguity and secret

reservation are legitimate in every case. I shall return to

this later.

White lie to save life and limb (44)

For English Catholics, French Protestants and Spanish

Jews, pretending to have changed their denomination or

religion was often the only way of saving their property,

often even life and limb, in early modern times. (45)

This was legitimate since the state and the churches

violated the freedom of religion with their repression. If

self-defence against the use of violence is lawful, then so

is a white lie to save life and limb. And if a white lie is

lawful on one's own behalf, then it is a fortiori

lawful for the protection of others.

The Bible provides an example. When Saul wanted to kill

his son-in-law David, David's wife Michal lied to the

messengers in order to enable him to escape (I. Sam. 19,

8-24). St Augustine and Kant may have thought of this when

they fundamentally rejected any white lie, even the one in

this specific case. In the fragment "Was heisst: Die

Wahrheit sagen" [What does it Mean: to Speak the

Truth], which Dieter Bonhoeffer wrote in a Gestapo

prison, he called the exponents of this rigorism "truth

fanatics ". (46)

In a hierarchy of values, the protection of innocently

prosecuted people carries more weight than the obligation of

being truthful. Those people who, in the Second World War,

hid Jews and, in so doing, invented a white lie or violated

a law, deserved admiration for their brave deed, not blame

or even punishment.

Stratagems (47)

In the Second World War, the Allies planned to invade the

French Atlantic coast from England. These plans were not

only kept secret but were combined with strategic deception.

This deception proved successful, and the Germans believed

that the invasion would take place at a different time, and

not in bad weather, and in a different place, not in

Normandy.

This case is easy to judge. If military force against an

aggressor is legitimate (jus ad bellum), then it

would not make any sense if the milder form of deception

should not be legitimate, either (ius in bello).

Warring parties expect stratagems to be used. Since Hugo

Grotius (48)

the international law of war (49)

has expressly declared stratagems lawful.

2.2 Illegitimate untruthfulness

My seven cases of illegitimate untruthfulness all come

from abroad, not one of them from Switzerland. However, this

does not mean to say that I am inclined to see the mote in

the other's eye but not the beam in my own. The simple

reason is that I have not found any spectacular Swiss case.

Apparently, exponents of bigger countries are more sorely

tempted than the politicians of small countries. Power is

liable to entice people into corruption, great power into a

high degree of corruption. Life in a small country may well

be governed by what George Bernard Shaw mockingly wrote:

"Virtue is insufficient temptation!"

Qualified mental reservation

The Harvard case collection describes the undercover

operation conducted by the US secret service, the CIA,

against the election of Salvador Allende in 1970. (50)

After no candidate had won an absolute majority, it was up

to the Chilean congress to choose from among the two leading

contenders. Although the CIA had spent eight million dollars

to prevent it, Allende was elected. The secret operation had

an aftermath in the American Senate when President Nixon

nominated the previous CIA chief, Richard Helms, to be the

US ambassador to Iran. During the hearings in the Senate,

the following dialogue took place: Senator Symington asked

Helms whether the CIA had tried to topple the Chilean

government. Helms replied: "No, sir." Senator Symington then

asked whether any monies had been given to opponents of

Allende's. Again the reply was: "No, sir."

According to the letter Helms's answers were correct. The

point at issue was not to topple the government but to

prevent the President's election. And no monies were given

to individuals but to groups which supported or rejected

candidates. This case of mental reservation cannot be

justified, for there is no excuse for deceiving a

democratically elected parliamentary organ, which is

entitled to clarify issues in a democracy, with a cheap

trick. Helms's behaviour undermined democracy and, in the

long term, contributed to a loss of confidence in the

American administration.

Thus not every mental reservation is legitimate. The US

Congress considered the question. When the members of the

House of Representatives are sworn in, they must swear to

take and comply with the oath upon the constitution without

any mental reservation: ""Do you solemnly swear that you

will support and defend the Constitution of the United

States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that you

will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that you

take this obligation freely, without any mental

reservation or purpose of evasion; and that you will

well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on

which you are about to enter. So help you God?"

Unlawful word of honour

The case of illegal, i.e. undeclared party donations to

Germany's chancellor Helmut Kohl is still widely talked

about. After the former chancellor first denied the

acceptance of such donations and then only admitted as much

as had been proved already, he refused to disclose the names

of the donors by invoking his word of honour.

The chancellor's behaviour was in glaring contravention

of the constitution, the party donation law, and the

official oath. A politician's word of honour "only deserves

the general public's respect as long as the action to which

he pledges his honour remains within the framework of the

law and on the ground of honesty. A word of honour which

refers to the maintenance of secrecy about jointly

perpetrated violations of the law does not meet this

requirement. In a case of conflict, it must therefore give

way to the readiness to enforce the law, as is in accordance

with the official oath sworn by high-ranking politicians

before the general public." (51)

Electioneering fraud

Sissela Bok's book refers to the case of the American

presidential campaign of 1964. (52)

The point at issue was the re-election of President Johnson

as against Senator Goldwater. In the campaign, the Vietnam

War played an important part. The situation in Vietnam was

constantly worsening. In the Johnson Administration, the

view had gained ground that an increase in the US commitment

could not be avoided. Making a big song and dance about

this, however, was not politic in the campaign. Senator

Goldwater championed an escalation of the war and did not

shy from nuclear threats, either. Conversely, Johnson was

depicted as a harbinger of peace. He himself proclaimed that

the overriding problem, the crucial point in the election

campaign was the question as to who would best be able to

preserve peace. The electioneering strategy proved

successful. Johnson was elected. A short time after the

election, he ordered a reinforcement of troops in South

Vietnam and the bombardment of North Vietnam. In order to be

elected, Johnson duped the American electorate in a

reproachable manner.

Disinformation of parliament and the

people

The 1964 electioneering fraud was systematic. It was no

isolated incident but part of a deception that went on for

years: a deception not of the enemy but of the country's own

population. There is evidence of this in the Pentagon

Papers. Hannah Arendt wrote a great essay about them. (53)

Still under Johnson's presidency, the US defence minister

Robert S. McNamara had commissioned a secret study to

provide a systematic picture of the history of the Vietnam

War. This study clearly revealed that for years, the

government had deceived the American public with purposively

optimistic information about how the war was progressing.

The deception of Congress in the Tonkin affair was

particularly grave. In August 1964, a US destroyer was shot

at by North Vietnamese torpedo boats in the Gulf of Tonkin.

The American government reacted to the alleged surprise

attack with indignation. The Pentagon Papers made it

clear that the incident was a concerted American

provocation. Its purpose was to get the US Congress to grant

the President the power of attorney for a stronger

commitment in this undeclared war. This then happened.

Someone involved with this secret study, Daniel Ellsberg,

informed the New York Times, which started to print

selected articles from the Pentagon Papers. In the

meantime, Johnson had been replaced by President Nixon, who

tried to stop publication by means of a court order.

However, the Supreme Court ruled in favour of the freedom of

the press and deemed that the Pentagon Papers were

not worth classifying. Subsequently, they were published in

their entirety.

The 47 volumes of the Pentagon Papers prove that

the American government had for years provided its own

people with an overoptimistic picture of the war. The

Vietnam War, which had never been declared and which ended

with a disastrous defeat of the

USA, was accompanied by a large-scale disinformation

campaign aimed at saving the US population's fragile

acceptance of the commitment. This short-term, dishonest

image policy resulted in a credibility gap with long-term

effects.

Rigged elections

The invocation of the name "Milosevic" will suffice!

Broken promise

It makes an essential difference whether the person

making the promise at the time believed in good faith that

he would be able to fulfill it and circumstances then

changed fundamentally in an unforeseeable manner, or whether

he secretly harboured the intention to break the promise

even at the time when he made it. The latter was the case

when the Hungarian uprising was crushed in 1956. The Soviet

government guaranteed the Hungarian Prime Minister Imre Nagy

and his Defence Minister Pál Maleter safe conduct to

the negotiations, and then killed them immediately.

Politician's official lie

The 1972-1974 Watergate affair is a case in point. In May

1972, the Democrats' headquarters in the Watergate Building

were broken into in order to tap the telephone of President

Nixon's Democratic rival. In June 1972, a second burglary

was attempted, this time to tap the phone of the chairman of

the Democratic Party. However, the burglars were caught,

arrested and tried. On the strength of an investigation

conducted by the Ministry of Justice, and of research

carried out by two journalists on the Washington

Post, it came to light that the break-ins had been

executed with the approval of Nixon's campaign chief, and

that they were merely the tip of an iceberg of numerous

dirty tricks, such as defamatory machinations against rivals

of Nixon's. The two journalists were later awarded the

Pulitzer Prize. President Nixon tried to wriggle out of it

by solemnly protesting that he knew nothing about it. He

repeated this statement several times, both before and after

his splendid re-election. After his re-election, the Senate

set up an investigation committee. When it became known that

all the conversations in the Oval Office of the White House

had been tape-recorded, the Justice Ministry's and the

Senate Committee's special investigator demanded that the

tapes be surrendered. Nixon refused this request with

reference to his executive privilege. However, the Supreme

Court ordered the disclosure of the tapes, which revealed

that Nixon had been informed three days after the second

burglary at the latest, and that he had therefore lied to

the American public several times. In July 1974, the House

of Representatives initiated the impeachment proceeding

against the President. Nixon escaped his impeachment by

resigning from office.

Perjury before a parliamentary investigation

committee

This leads us to the Iran/Contra affair of 1984-1986. It

is documented in the case collection of Harvard University. (54)

The affair was an undercover action since it was known to

only a few people in the National Security Council and in

the CIA. President Reagan was partially informed, the

Secretary of State and the Defence Minister were as good as

not informed at all, and nor were Congress and the

committees responsible for secret operations. The double

affair consisted, first, in the secret sale of weapons to

Iran for the liberation of American hostages in Lebanon and,

second, in the use of the proceeds of the arms sales for the

support of the Contra rebels against the Sandinista regime

in Nicaragua. When the deal came to light, Congress

conducted an investigation that lasted several months.

During the interrogation, the two main protagonists, Admiral

John Poindexter and Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North, lied to

the Congress committees and sabotaged the investigation by

destroying and forging documents. Even so, Congress managed

to expose the affair. North was cashiered, and Poindexter

had to resign from this office as the President's security

adviser.

The main protagonists tried to exonerate themselves by

saying that the arms export had not been carried out

directly but through third parties, that no budgetary funds

released by Congress had been used, and the President had

basically given his consent, and that lies and cover-ups had

been necessary because the "enemy" was listening in. Both

covert operations were illegal since there was a ban on arms

exports to Iran and because Congress had prohibited any

support of the Contra rebels. Lying to parliament, and even

more so committing perjury before a parliamentary

investigation committee, cannot be justified in a democracy

by any manner of means.

These horror stories involving different types and cases

of whopping lies and other untruthfulness might create the

impression that politics is a thoroughly dirty business even

in constitutional democracies. This conclusion would,

however, be premature. Although we are unaware of the

percentage of undetected cases, we do not know when and how

often politicians have been prevented from untruthful words

and deeds by their personal integrity or for fear of the

consequences of being found out.

3 Incentives for truthfulness

Are there any incentives for truthfulness in politics? Or

more precisely: are there any incentives in person-oriented,

institution-oriented or results-oriented ethics? (55)

-

Person-oriented political ethics strive towards an

approximation to morally good politics through good office

holders,

-

institution-oriented ethics do so through good

institutions, and

-

results-oriented ethics through good

results.

3.1 Person-oriented political

ethics

In November 1997, the General Secretary of the United

Nations was presented with a draft Universal Declaration

of Human Responsibilities. (56)

The draft was conceived of as a counterpart to the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which had been

announced by the United Nations in 1948. Fifty years on, the

declaration of rights was complemented by a declaration of

responsibilities.

Art. 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human

Responsibilities says: "Every person has a

responsibility to speak and act truthfully. No one,

however high or mighty, should speak lies. The right to

privacy and to personal and professional confidentiality is

to be respected. No one is obliged to tell all the truth to

everyone all the time."

At first sight, this may sound naive. But on closer

inspection, one is amazed to find that the author of the

Universal Declaration of Human Responsibilities is

none other than the InterAction Council, an association of

former heads of state and heads of government from all five

continents. Its Honorary Chairman is Helmut Schmidt, former

Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, and its

present Chairman is Malcolm Fraser, former Prime Minister of

Australia. Twenty-five of the elder statesmen signed the

draft declaration, among them Switzerland's former Federal

Councillor Kurt Furgler.

The draft of the Universal Declaration of Human

Responsibilities was not simply dashed off. Rather, it

was prepared in two expert meetings and two annual general

meetings of the InterAction Council. The main author was the

Swiss theologian Hans Küng, who had initiated a

worldwide movement with his book Global Responsibility,

In Search of a New World Ethic in 1990. The aim of the

movement is the establishment of a modicum of shared ethical

values, fundamental attitudes and standards which can be

agreed upon by, if at all possible, all the religions,

regions and nations. In 1993, the Parliament of the World's

Religions issued a declaration regarding a global ethic. (57)

This declaration, as well as Hans Küng's book A

Global Ethic for Global Politics and Economics,

published in 1997, emphasise the obligation of truthfulness. (58)

The publication of the Universal Declaration of Human

Responsibilities triggered off a partially fierce debate

in the German weekly newspaper Die Zeit. (59)

This is not the place to go into the ins and outs of that

debate, but a further-reaching result of the controversy has

an immediate connection with the obligation of truthfulness.

In his opening article, Helmut Schmidt had laid a false

track. (60)

Like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of

1948, the Declaration of Human Responsibilities is

not legally binding; they are both declarations of intent.

Yet the Declaration of Human Rights resulted in treaties

that are binding under international law, particularly the

two UN Human Rights Conventions of 1966. Now Helmut Schmidt

hoped that the Declaration of Human Responsibilities

would have a legal impact in a comparable manner. That was a

wrong track. Why?

There are legal responsibilities, and there are ethical

responsibilities. The distinction here used to be between

perfect and imperfect responsibilities. (61)

Tax liability, conscription, electoral duty, the prohibition

of torture, the prohibition of theft, the protection of the

civilian population in times of war, etc., can be

established as legal responsibilities. But the

"responsibility to treat all people in a humane way" (Art.

1) or the golden rule "What you do not wish to be done to

yourself, do not do to others" (Art. 4) are inappropriate

for a legally binding form. The same applies to the

obligation of truthfulness of Article 12.

If we recognise that the obligation of truthfulness is

not meant as a legal responsibility but as a moral appeal,

then it has the potential to sharpen office holders'

consciences. It does not only merit inclusion in a

Universal Declaration of Human Responsibilities, but

also in professional codes of conduct for politicians or in

newly formulated political oaths, which office holders have

to swear in most countries. Understood in this way, Article

12 of the Universal Declaration of Human

Responsibilities is not naive. And generally speaking,

the wish appears to be justified that the Declaration of

Human Responsibilities should be debated by the United

Nations and that it should be adopted as a declaration of

intent, possibly in an amended form.

3.2 Institution-oriented political

ethics

Moral appeals on their own are effective only up to a

point. Claus Offe wrote: "Politics are only as honest as

their institutions are effective..." (62)

The qualifier "only" strikes me as exaggerated. However,

institutions are very important as incentives for

truthfulness. In a democracy, such institutions are the

opposition, parliament, the judiciary, and the media. If

they work well, they will discourage lies, deception and

other kinds of untruthfulness.

In four of the cases discussed above, the democratic

institutions functioned, albeit with losses, and only after

the event. In the German party donation scandal, the media,

parliament and the parties worked together. In the affair of

the Pentagon Papers, it was a combination of an

individual citizen's personal courage, the media, and the

Supreme Court. In the Watergate and Irangate cases, the

checks worked thanks to the interaction between the media,

the Justice Ministry, and Congress. Such cases may well act

as signals. Any future politician will have to think about

whether the risk of untruthfulness is worth it. He is well

aware now that public response will be very severe. Those

who are caught will have to expect a hiatus in their career,

or its very end.

3.3 Results-oriented political

ethics

Political trust and mistrust are the result of, among

other things, truthful or untruthful behaviour. Truthfulness

fosters trust, untruthfulness destroys it. Trust is a

fundamental category in a democracy, in a constitutional

state and in international law. The principle of trust is

the foundation of all law. Politicians want to be elected or

re-elected, i.e. they must make an effort to win the

electorate's trust. Political parties want to secure as big

a share as possible in parliamentary and government power,

i.e. they must also make an effort to win the electorate's

trust. It is not only the politicians and the political

parties, however, that depend on the trust of the electorate

and, in a direct democracy, of the voters; rather, trust and

mistrust are also directed at institutions, at parliament,

government, the judiciary, the constitutional state,

democracy itself. In a democracy, any policy can only be

implemented in the long term if it is accepted by the

electorate, i.e. it again depends on trust. Elections and

referendums are a trial of trust. In parliamentary

democracies, votes of confidence or of no confidence may

take place between election times. Opinion polls determine

the measure of trust placed in persons, parties and

institutions. An official ethical code enjoins US senators

and representatives to behave so as not to bring Congress

into disrepute. (63)

Most recently, "truth commissions have been set up, for

instance in South Africa, to create a new basis of trust

through reconciliation after bloody conflicts.

Of course, truthfulness and untruthfulness are not the

only criteria of trust and mistrust. Other criteria include

political successes and failures, or lawful and unlawful

behaviour. However, the results of polls and media reports

reveal very clearly that the politically interested general

public responds very sensitively, angrily, indeed

indignantly to untruthfulness. During the Vietnam War and in

the wake of Watergate, the American's trust in their own

government shrank drastically: from three quarters in 1964

to a quarter in 1980. (64)

Similar collapses of confidence could be observed as a

consequence of the scandal surrounding the donations to the

German Christian Democratic Union party and the nuclear

submarine disaster in Russia. Politicians', political

parties' and institutions' interest in preserving and

enhancing trust is a positive incentive for

truthfulness.

Conclusion

In the introduction, I quoted Václav Havel. To

conclude, I would like to return to him. 2500 years of

political ethics came and went until a statesman, namely

Havel, raised truthfulness to the rank of a decisive quality

of politics. Max Weber, in his famous lecture Politik als

Beruf [Politics as a Profession], demanded three

prime characteristics from politicians:

- passion for the cause,

- a sense of responsibility,

- and Augenmass. (65)

[quick perception and sense of judgement]

Should not a fourth characteristic be added:

Bibliography

Classic texts that have been published in various

editions are usually quoted in such a manner that the

passages in question can be found in any edition.

Aristotle, Nicomachian Ethics

Aegidius Romanus (Colonna) (1968), De regimine

principum libri III, unchanged reprint, Rome 1556,

Frankfurt

Arendt, Hannah (1972), Wahrheit und Lüge in

der Politik, Munich

Augustinus, Aurelius (1900), "De mendacio" and "Ad

Consentium contra mendacium", Corpus scriptorum

ecclesiasticorum latinorum, Vol. XXXXI (sect. V pars

III), Prague, pp. 411-466/467-528

Bok, Sissela (1980), Lügen, Vom täglichen

Zwang zur Unaufrichtigkeit, Reinbek bei Hamburg;

orig. Lying: Moral Choice in Public and Private

Life, Pantheon Books, New York, 1978

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich (1963), Ethik, 6th ed.,

Munich

Burckhardt, Jacob (1921), Weltgeschichtliche

Betrachtungen, Stuttgart

Cicero, Marcus Tullius (1984), De officiis /

Vom pflichtgemässen Handeln, Latin/German,

Stuttgart

Geismann, Georgi/Oberer, Hariolf, eds. (1986), Kant

und das Recht der Lüge, Würzburg

Grotius, Hugo (1950), De iure belli ac pacis libri

tres, Drei Bücher vom Recht des Krieges und des

Friedens, Paris 1625, new German text and preface by

Walter Schätzel, Tübingen

Gutmann, Amy/Thompson, Dennis, eds. (1990), Ethics

and Politics, Cases and Comments, 2nd ed.,

Chicago

Häberle, Peter (1995), Wahrheitsprobleme im

Verfassungsstaat, Baden-Baden

Havel, Václav (1989), Versuch, in der

Wahrheit zu leben, Reinbek bei Hamburg

Havel, Václav (1991), Angst vor der

Freiheit, Reden des Staatspräsidenten, Reinbek

bei Hamburg

Kant, Immanuel (1963), Werke in sechs

Bänden, Darmstadt

Kemper, Peter, ed. (1993), Opfer der Macht,

Müssen Politiker ehrlich sein?, Frankfurt

a.M.

Küng, Hans (1978), Wahrhaftigkeit, Zur Zukunft

der Kirche, Freiburg i.Br.

Küng, Hans (1990), Projekt Weltethos,

Munich; tr. Global Responsibility, In Search of a New

World Ethic, SCM Press, London 1991

Küng, Hans/Kuschel, Karl-Josef, eds. (1993),

Erklärung zum Weltethos, Die Deklaration des

Parlaments der Weltreligionen, München

Küng, Hans (1997), Weltethos für

Weltpolitik und Weltwirtschaft, München; tr.

Global Ethic for Global Politics and Economics

Laros, Matthias (1951), Seid klug wie die Schlangen

und einfältig wie die Tauben, Frankfurt a.M.

Machiavelli, Niccolò, Il Principe

Machiavelli, Niccolò (1990), Politische

Schriften, Herfried Münkier (ed.), Frankfurt

a.M.

Martel, Andrea (2001), Vom guten Parlamentarier,

Eine Studie der Ethikregeln im US-Kongress, Berne

Montaigne, Michel de (1985), Essais, Zurich

Müller, Gregor (1962), Die

Wahrhaftigkeitspflicht und die Problematik der

Lüge, Freiburg i.Br.

Münkier, Herfried (2000), "Das Ethos der

Demokratie. Über Ehre, Ehrlichkeit, Lügen und

Karrieren in der Politik", Politische

Vierteljahresschrift, 41st year, June 2000, No. 2,

pp. 302-315

Orren, Gary (1997), "Fall from Grace: The Public's

Loss of Faith in Government", Joseph S. Nye Jr./Philip 0.

Zelikow/David C. King (eds.), Why People don't Trust

Government, Cambridge, Mass.

Pascal, Blaise (1998), Oeuvres

complètes, Vol. 1, Paris

Plato, Politeia

Pufendorf, Samuel von (1994), Über die Pflicht

des Menschen und des Bürgers nach dem Gesetz der

Natur, Frankfurt a.M. and Leipzig

Revel, Jean-François (1990), Die Herrschaft

der Lüge, Wie Medien und Politiker die

Öffentlichkeit manipulieren,

Vienna/Darmstadt

Riklin, Alois (1995), "Politische Ethik", Helmut

Kramer (eds.), Politische Theorie und

Ideengeschichte, Vienna, pp. 81-104

Schmidt, Helmut, ed. (1997), Allgemeine

Erklärung der Menschenpflichten, München;

The English text on

interactioncouncil.org

> Human Responsibility

> .../publications/universal-declaration-human-responsibilities

Schockenhoff, Eberhard (2000), Zur Lüge

verdammt - Politik, Medien, Medizin, Justiz, Wissenschaft

und die Ethik der Wahrheit, Freiburg i.Br.

Soeffner, Hans-Georg (1998), "Erzwungene

Ästhetik. Repräsentation, Zeremonien und Ritual

in der Politik", Herbert Willems/Martin Jurga (eds.),

Inszenierungsgesellschaft. Ein einführendes

Handbuch, Opladen, pp. 215-234

Sternberger, Doif (1988), "Wiessee und Sinigaglia, Zu

Hitlers Mordaktion vom 30. Juni 1934", in: Breitling,

Rupertt/Gellner, Winand (eds.), Politische Studien zu

Machiavellismus und demokratische Legitimierung, Teil

I der Politischen Studien zum 65. Geburtstag von Erwin

Faul, Gerlingen

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica

Weber, Max (1964), Politik als Beruf,

Berlin

Zagorin, Perez (1990), Ways of Lying.

Dissimulation, Persecution, and Conformity in Early

Modern Europe, Cambridge Mass.

(1) Burckhardt

1921, pp. 33/96/140

back ^

(2) Machiavelli

1967, 1126, p.88

back ^

(3) Arendt 1972, pp.

8/44

back ^

(4) Luhmann, in:

Kemper 1993, p.40

back ^

(5) Ibid., p.34

back ^

(6) Ibid., p.39

back ^

(7) Soeffner 1998,

p.224 (quoted after Münkler 2000, p.303)

back ^

(8) Revel 1990, p.

11

back ^

(9) Nicomachian

Ethics, 1127 a 20-1128 b 9

back ^

(10) De

mendacio and Contra mendacium

back ^

(11) Summa

theologica, II-II q. 109-112

back ^

(12) Über

ein vermeintes Recht aus Menschenliebe zu lügen

(Kant, Vol. 4, pp. 637-643)

back ^

(13) De regimine

principum, pp. 80-82

back ^

(14) Havel 1989

back ^

(15) Havel 1991,

pp. 8-17

back ^

(16) Ibid., p.83

back ^

(17) Havel 1989,

pp. 84-86

back ^

(18) St Thomas

Aquinas, II-II q. 109-112

back ^

(19) Montaigne

1985, pp. 79-83 ("Von den Lügnern" [Of the

liars])

back ^

(20) Augustinus

1968, pp. 411-466/467-528; Müller 1962, pp. 52-56

back ^

(21) Schockenhoff

2000, p.59

back ^

(22)

Geismann/Oberer 1986

back ^

(23) Ibid., pp.

23-25

back ^

(24) Kant 1963,

Vol. 4, pp. 637-643

back ^

(25) Ibid., p.562

("Metaphysik der Sitten" [The Metaphysics of

Morals])

back ^

(26) Plato, 389 b-d

back ^

(27) Ibid.,

414c-415b

back ^

(28) Ibid., 459c-e

back ^

(29) Machiavelli,

Il Principe, Chap. XVIII

back ^

(30) Cicero, De

officiis, II/44, p. 181

back ^

(31) Machiavelli

1990, pp. 375-379

back ^

(32) Sternberger

1988, p.85

back ^

(33) Grotius 1950,

111/1

back ^

(34) Pufendorf

1994, 1/10

back ^

(35) Müller

1962, pp. 271-279/325-327/330-334

back ^

(36) Bok 198O, p.

219

back ^

(37) Ibid., pp.

98-116

back ^

(38) Ibid., pp.

117-135

back ^

(39) Ibid., pp.

119-132

back ^

(40) Ibid., pp.

76/78

back ^

(41) Ibid., p.213;

Schockenhoff 2000, p.37

back ^

(42)

Gutmann/Thompson 1990, pp. 39-74

back ^

(43) Pascal 1998,

p. 679

back ^

(44) Laros 1951, p.

37; Bok 1980, pp. 65/136; Schockenhoff 2000, pp. 106-108

back ^

(45) Zagorin 1990;

Schockenhoff 2000, p. 89

back ^

(46) Bonhoeffer

1963, p. 388

back ^

(47) Ibid., p.391;

Bok 1980, p. 178

back ^

(48) Grotius 1950,

III/1, VI

back ^

(49) The Hague Law

of Land Warfare, Art. 24

back ^

(50)

Gutmann/Thompson 1990, p. 44

back ^

(51) Schockenhoff

2000, p.324

back ^

(52) Bok 1980, pp.

207-209

back ^

(53) Arendt 1972,

pp. 7-43

back ^

(54)

Gutmann/Thompson 1990, pp. 48-60

back ^

(55) For an

explanation of this differentiation, cf. Riklin 1995

back ^

(56)

Text on:

interactioncouncil.org

> Human Responsibility

> .../publications/universal-declaration-human-responsibilities

back ^

(57) Towards a Global Ethic: an Initial Declaration,

> google.ch/search?q=Towards a Global Ethic: An Initial Declaration cpwr.org

[no more] on

cpwr.org/resource/global_ethic.htm (cpwr.org/calldocs/EthicTOC.html) [as in the printed edition]

back ^

(58) Küng

1997, pp. 108-112

back ^

(59) Die

Zeit, No. 41 of 3/10/1997, No. 42 of 10/10/1997, No.

43 of 17/10/1997, No. 44 of 24/10/1997, No. 45 of

31/10/1997

back ^

(60) Die

Zeit, No. 41 of 3/10/1997

back ^

(61) Küng in:

Schmidt 1997, p.92

back ^

(62) Offe in:

Kemper 1993, p.131

back ^

(63) Martel 2001,

p. 71

back ^

(64) Orren 1997,

pp. 80f

back ^

(65) A term that

does not readily translate into English. Literally

"measurement by eye", it means precisely that for a

craftsman who, with a quick and experienced eye, is

capable of measuring dimensions without the application

of a measuring tape. At an abstract level, the term

accordingly denotes a quick faculty of perception

combined with a sound sense of judgement.

back ^

|